Our process

Our process

Free Intro

Schedule your free intro to discuss your goals, our services, and assess your current fitness.

Personalized Plan

We’ll tailor your workout plan based on your current fitness.

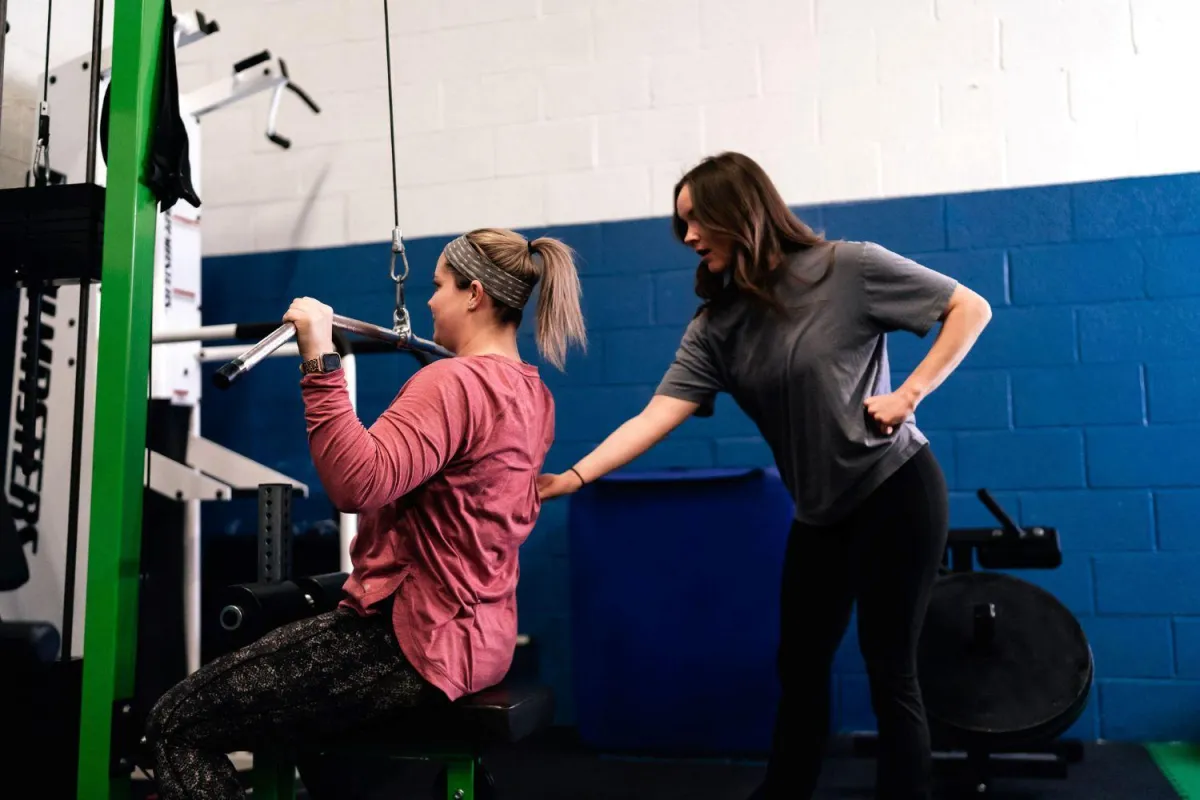

Results

With our attention to detail and science-backed programming, we deliver sustainable results.

Free Intro

Schedule your free intro to discuss your goals, our services, and assess your current fitness.

Personalized Plan

We’ll tailor your program to your current fitness, setting you up for

long-term success.

Results

With our attention to detail, science-backed programming and self-paced training sessions, we deliver sustainable results

experience the paragon difference

Tired of nagging injuries from random fitness programs, quick fixes that land you back at your starting point and navigating your health alone? Schedule your Free Intro to learn how we support you beyond a good sweat.

Our Programs

Semi-Private

Training

Personal training in a small group setting, with only four members per coach.

Personal

Training

Personal training is a one-on-one or partner experience.

Two Week

Trial

Not sure if Paragon is right for you? No sweat. We offer a two week trial for $49 so you can decide!

Hear it from our community

Address

Paragon Health & Fitness

19970 Ingersoll Dr.

Rocky River, OH 44116

Copyright © 2025 Paragon | All rights reserved | Designed By Zenplanner